Acting for the landowner

Private roads disputes - October 2023

Private roads disputes - October 2023

This resource will assist in identifying whether your client is dealing with a legal problem in relation to their ownership of a private road that has sustained damage following a disaster and which is used by other people.

It will also explain what their rights and obligations are when dealing with it.

A landowner has a duty of care to repair a private road where it has been damaged by a disaster where it is reasonably foreseeable for harm to occur to an invitee or trespasser.

This resource includes:

a flowchart

determining whether there is an easement and reviewing easement terms

advising your client on duty of care owed by landowner to invitees or trespassers

costs disputes

template letters

An easement is an arrangement that gives someone the right to access and use land for a specific purpose, while the legal title or ownership of the land remains with the owner.

You will need to determine whether there is a registered easement relating to the road.

To do this, review the title search you obtained when establishing road ownership. In addition to current owner(s) of the property and the land description, it will show any registered interests, including easements, relating to the land and their terms.

This section includes:

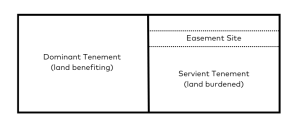

To have a valid easement there must be a benefited parcel and a burdened parcel of land, referred to as the dominant and servient tenements respectively. This is shown in the diagram below:

There are various types of easements that may be relevant to private roads. The most common, and discussed for the purposes of this resource, are an easement for the right of carriageway and an easement of necessity.

A right of carriageway is also known as a right of way. A right of carriageway is a particular type of easement which provides one party the right to travel over the land of another.

Schedule 8, Part 1 of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW) provides for the standard construction of expression for a right of carriageway:

‘Full and free right for every person who is at any time entitled to an estate or interest in possession in the land herein indicated as the dominant tenement or any part thereof with which the right shall be capable of enjoyment, and every person authorised by that person, to go, pass and repass at all times and for all purposes with or without animals or vehicles or both to and from the said dominant tenement or any part thereof.’

An easement of necessity arises when land is ‘landlocked’, meaning to access the land you must travel over someone else’s land. An easement of necessity does not arise when there are other options to access the site.

An easement of necessity is an easement created by implied grant or reservation and without which the dominant tenement could not be used. No easement of necessity is implied where alternative rights exist, for example, if an alternative access exists, even though that access may be indirect or inconvenient. An easement of necessity ceases if the necessity ceases. An easement of necessity may only be used for purposes appropriate to the use of the land at the time the easement arose.

There are strict prerequisites for an easement of necessity, and they are only available in circumstances where absolutely required.

If there is an easement, it is crucial to review the relevant easement terms to confirm the repair and maintenance requirements and who is responsible as well as the proportion the costs are to be shared.

If there is a registered easement to access the private road by neighbours, as per Schedule 8B(7) of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW), the costs of maintenance and repair in respect of an easement that gives a right of vehicular access or personal access are to be borne by the persons concerned in the proportions specified in the easement or in equal proportions if unspecified.

It is important to review the terms of the registered easement prior to requesting an interested easement party contributes to the costs of repairing the road. It is also important to advise the landowner that they keep all receipts or invoices in relation to the maintenance or repair of the road.

If there is no reference to cost proportions in the easement, costs are to be paid in accordance with Schedule 8B, section 7 of the Conveyancing Act 1919 (NSW), it is to be in equal proportions.

Following damage to a private road where an easement is registered on title, it is recommended that the landowner provide a written notice of the damage and proposed costs to be shared to repair the damage to the easement holder(s).

A template letter is provided here to be completed with the relevant details:

Following the provision of the above letter, the subsequent courses of action are:

If costs are agreed, the landowner may undertake the required repairs for the road in accordance with any easement terms and provide an invoice to the other easement holders(s) to make the payment.

2. Costs not agreed

If the relevant easement parties do not contribute to the costs of repair, the landowner may demand payment of the amount they owe in writing.

A template Letter of Demand is provided here to be completed with the relevant details:

Discussions/negotiations may commence between relevant parties regarding the liability for the costs of maintenance and repair of the roads and who is responsible for completing repairs. It is highly recommended and preferred the parties engage in alternative dispute resolution (ADR) methods prior to commencing a court claim.

Alternative dispute resolution options are set out on this page:

If ADR is unsuccessful in resolving the costs dispute, the landowner may bring a court claim in the relevant jurisdiction to recover costs owned.

More information regarding court claims is provided here:

Section 5(1) of the Roads Act 1992 (NSW) establishes that members of the public have the right to ‘pass along a public road (whether on foot, in a vehicle or otherwise) and to drive stock or other animals along the public road’.

The same right is not awarded in respect to private roads. As such, a neighbour of someone with a private road cannot use that private road without an appropriate easement or agreement. To establish a right to access and/or use a private road, an easement must be established.

If there is no other way to access their land other than the damaged road, an easement of necessity may apply. However, if there is another way to access the property the neighbouring landowner (your client) is not required to agree to establishing an easement.

Where there is no easement applicable to the private road dispute, the landowner of the private road may prohibit access to and use of the private road by means such as erecting gates or locking existing gates.

If the road is damaged due to a disaster, even without an easement, the landowner still owes a duty of care to invitees and trespassers that may use the road, if it is reasonably foreseeable for harm to occur to them. In the section below, we provide guidance on advising the landowner on their duty of care and how to mitigate risk of liability for a breach of their duty of care.

Landowner duty of care extends to usage of private roads. A landowner owes a duty of care to invitees and trespasses to avoid/reduce reasonable harm. Therefore, a landowner of a private road will owe a duty of care requiring repair of a road which has sustained damage following a disaster if it is reasonably foreseeable to the landowner that harm may occur to an invitee or trespasser if they use a damaged private road.

It is unlikely that damage occurring from a disaster mitigates the landowner’s liability and responsibility.

Landowners should be advised as to their duty of care, the law’s application to their specific circumstances, and what consequences they may face if they are found to be in breach.

This section includes:

personal injury claims

relevant law and regulation, including:

A private road owner may be required to pay damages to a harmed person where the owner is determined to be responsible for the respective harm resulting from use of the road.

If a private road owner is determined to be responsible for harm by a court as a result of not taking action to repair the private road following a disaster, when the owner knew or should have known it was damaged, the owner may be required to pay compensation, known as damages, to the harmed person. Not knowing that the road is damaged may not be enough to escape responsibility.

This is established in the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) and case law.

If there is an easement over the private road, the owner (not the holder of the registered easement) is still responsible for any harm caused to someone using the road if it is damaged following a disaster and is still responsible for repairing the road.

According to the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW), Section 5B, which establishes a landowner’s duty of care:

One of the leading statements on the extent of the duty of care owed by a landowner was made by Justice Deane in the High Court in Hacksaw v Shaw (1984) 155 CLR. In this case, Justice Deane stated:

“Where the visitor is lawfully upon the land, the mere relationship between the occupier on the one hand and the invitee or licensee on the other will of itself suffice to give rise to a duty on the part of the occupier to take reasonable care to avoid a foreseeable risk of injury to her or him.

When the visitor is on the land as a trespasser, the mere relationship of the occupier and the trespasser in which the trespasser has imposed upon the occupier will not satisfy the requirement of proximity. Something more will be required. The additional factor or combination of factors which may … supply the (required) degree of proximity or give rise to a reasonably foreseeable risk of relevant injury are incapable of being exhaustively defined or identified. At the least they will include either knowledge of the actual or likely presence of a trespasser or reasonable foreseeability of a real risk of such presence”

A private road landowner will be liable for harm or damage caused to a trespasser or invitee if there is a reasonably foreseeable risk of harm or damage occurring (Hacksaw v Shaw).

In Burnie Port Authority v General Jones Pty Ltd (1994) (High Court) the appellant was found liable for damages caused by the negligence of its independent contractor. The contractor was carrying out unguarded welding operations which resulted in a fire spreading to adjoining cold rooms occupied by the respondent and ruining the respondent’s frozen vegetables.

In Weber v Greater Hume Shire Council (2019) (NSWCA), Greater Hume Shire Council operated a waste disposal site. A fire ignited in the tip and quickly spread, reaching Gegorery where it destroyed homes and personal possessions of several residents including the appellant. It was held:

The most likely cause of the fire was spontaneous combustion, however it was not necessary for the Court of Appeal to be satisfied on the balance of probabilities that spontaneous combustion was the cause. The only other likely causes were the lensing effect of glass and arcing of a vehicle battery. As such, the Court of Appeal considered it was more probably than not that one of these was the cause of the fire.

The Council failed to take a number of precautions to avoid the risk of fire igniting and spreading from the tip. Within the tip, these precautions included reducing dried vegetation in the tip and slashing the glass between the piles of waste and between the waste and boundary fence. Other precautions which the Court of Appeal accepted should have been taken by the Council included compacting and covering the waste and maintaining a fire break around the tip.

It was still necessary to consider whether the limited resources available to Council meant that those precautions were beyond those which should have been reasonably undertaken. For that purpose, this required considering the burden of adopting those precautions only at waste disposal facilities operated by the Council, and not on other land owned or occupied by the Council. In this respect, while the evidence showed that the tip operated at a loss (as expected), there was evidence that the Council received unallocated grants and maintained a waste management fund, for which the actual expenditure prior to the fire was less than the budgeted expenditure.

This indicated that here had been ‘ample funds’ available to the Council to take all the identified precautions. Consequently, the Court of Appeal concluded there was no evidence that the Council was reasonably precluded from taking those precautions.

In McInnes v Wardle (1931) (High Court) a contractor was engaged by the defendant to fumigate rabbits. The normal practice was to clear the bracken fern by burning. The contractor lit a fire which escaped to the plaintiff’s neighbouring property and caused damage. Judgement was awarded to the plaintiff and it was determined the landowner was negligent. The court pointed out that:

Grass and scrub are usually very dry during the Australian summer and that fires spread with great rapidity. It was observed that the statutory prohibitions against lighting fires during summer months demonstrated that the defendant should have foreseen and guarded against the danger of burning ferns and undergrowth as a means of controlling rabbits.

In Yeung v Santosa Realty (2020) (Victorian Supreme Court) it was held the duty to inspect, detect and report on obvious hazards had been delegated by the owner to the real estate agent. This decision confirms the legal proposition that the duty of a landlord to take reasonable precautions (by routine inspection of rental premises) to avoid foreseeable risk of injury can be delegated by engaging a competent contractor (managing real estate agent).

A private road owner may be required to pay damages to a harmed person where the owner is determined to be responsible for the respective harm resulting from the use of the road.

If they sustained harm as a result of using the landowner’s damaged private road, a road user may initiate Alternative Dispute Resolution or make a claim in court.

Any disputes in regard to private road liability may be brought in the Supreme Court of NSW and any claims made for a breach of liability may be brought by application in the competent jurisdiction dependent on the monetary amount claimed.

A claim for any breach resulting in personal injury is to be brought within 3 years from the date the negligence occurred as required by the Limitation Act 1969 (NSW).

How to advise and act for your client if a claim is brought against them for harm or damage caused to a road user is outside the scope of this resource. See the following section on how to make a referral to Justice Connect for pro bono legal assistance.

Justice Connect connects eligible individuals, small business owners and primary producers and community organisations affected by disasters like floods, bushfires, cyclones, and other extreme weather events, with free legal help.

We may be able to match your client with one of our pro bono lawyers for assistance with a private road dispute.

I need to refer someone – Refer to Justice Connect

LawAccess is a free government service that provides legal information and referrals, including to Legal Aid NSW, for people with a legal problem in NSW. See their website for more information on how they can help.

This resource was last updated on 31 October 2023. This is legal information only and does not constitute legal advice. You should always contact a lawyer for advice specific to your situation. You can view our full disclaimer here: Disclaimer and copyright for our Disaster Legal Support Resource Hub – Justice Connect